Where Tomato Brown Rugose Fruit Virus ( ToBRFV) is detected, growers must find the right balance between continuing with their normal levels of hygiene or taking extra hygiene precautions. This article wants to help find the right balance and determine which measures will be useful – and why – for your location. Slowing down the spread of the virus after it has been detected may potentially lead to the production of a better crop and a higher yield compared to no action taken. "The virus moves with plant material, with water, with people, with equipment and through the air", says Harmen Hummelen; Vegetables By Bayer Field Quality Lead, explaining further on how to act.

Basics

There are 3 basic steps:

- Make sure that plant growth is good by adjusting the climate and reducing crop stress.

- Ensure basic hygiene is in place. For example, this means – without exhaustive hand washing, cleaning equipment, and reducing direct contact with infected plants by people and equipment.

- Stop the virus moving through the greenhouse. ToBRFV is mechanically transmitted, so it can 'hitchhike' to the next plant on all kinds of materials and equipment. These transport routes have to be blocked as much as possible.

This article will focus on point #3.

People and virus transmission

People pose a high risk of spreading the virus. Not every person poses the same risk or even considers him- or herself as being a risk. Creating awareness about how virus transmission happens is the first step towards managing the spread.

Workers are the largest group who interact with the crop every day. There may be full-time employees and temporary workers. It may be that some workers can work in different tomato greenhouses yet use the same car or live in the same house. Their personal belongings may be mixing, for example shoes next to each other or even exchanging shoes. This is an example of how the virus can be moved from greenhouse to greenhouse through clothes or shoes off-site. Some workers may also work at multiple locations, sometimes on the same day.

Workers may grow tomatoes at home or bring store-bought tomatoes for lunch. These risks need to be mentioned to the workers and, if possible, reduced.

Owners and managers are also a high risk because they may bypass hygiene protocols to complete actions quickly. But any interaction with plants, equipment, or structures can lead to the virus being picked up and moved. A quick visit by a manager or owner is enough to help the virus move to another plant. It is often very difficult for managers, owners, and the parents of owners to adapt to a new way of working and not to be able to 'quickly' visit a greenhouse.

External visitors are always seen as a high risk, particularly if those people visit other tomato or horticultural locations. Some of these visitors are fully aware of the risk and take good precautions. Other visitors, like contractors repairing or building, are often not plant- or 'green'-minded and do not see any risks. Both groups should follow strict protocols before entering the location. This includes not allowing equipment from other locations to enter the greenhouse without cleaning.

Visualize transport routes of the virus

The virus moves with plant material, water, people, equipment, and through the air. The virus is not visible, so workers can find it difficult to visualize or imagine. A helpful tool can be to draw a picture of the greenhouse with all the routes that plants, people, water, and equipment follow, and which doors are used.

All these steps can be listed, and a risk assessment can be carried out. Many of these steps are in the mind of you as a grower or technician, but it is also very useful to get other people, including workers and managers, to add to the list. This helps everyone to know all the risks and reduces the risks of some steps in the process being forgotten.

Reviewing the list 1 or 2 times a year helps keep people alert to the risks and keeps the assessment up to date. Reviewing can be done by management, but asking workers to join is really helpful in hearing what is really done in the greenhouse. Workers helping with the risk assessment will also feel more involved and will take better care and can be ambassadors in the greenhouse for better hygiene.

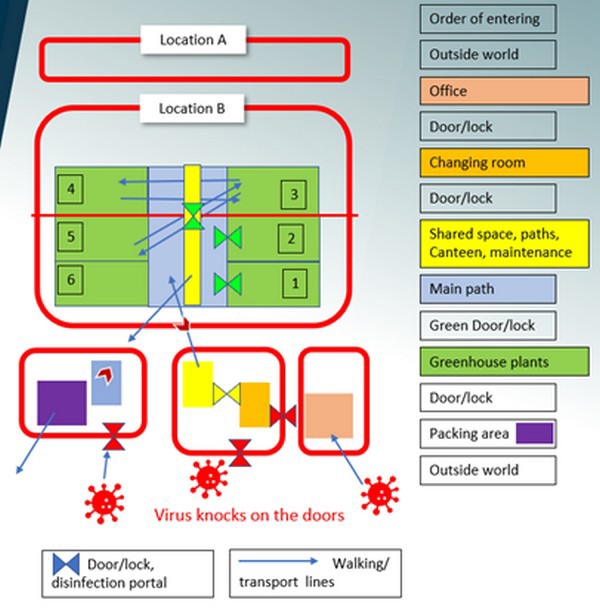

An example of a drawing of the greenhouse is shown in the below picture. Lines are drawn to show walking routes, and doors and disinfection locks are also shown. If this overview of the greenhouse is printed on a big piece of paper and put in an area such as the canteen people are more likely to discuss it. Discussion creates awareness and people will be more involved and supportive.

Figure: Example of schematic drawing of a greenhouse showing all the people and equipment moving lines. Making such an overview helps identify all possible routes of entry and spread of a virus in the greenhouse.

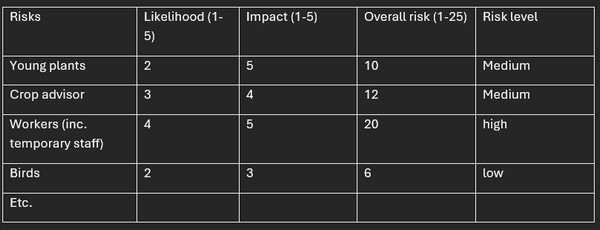

Example, Risk assessment table

Examples are given of risks, along with example scores for the likelihood, impact, and risk level (1 being lowest, 5 being highest). Every company should make their own list of risks and determine their likelihood, impact, and risk level. Overall risk is determined by multiplying the likelihood with the impact.

If risks are known, actions can be defined and executed.

Extra measures after virus infection

Hand washing and changing shoes and clothes is becoming a basic hygiene measure at many locations. This creates a cost, and it can be discussed if this has to be done the whole year (however, it should be considered whether the potential cost of lost crops due to ToBRFV is likely to be higher than the costs of good hygiene). Stricter rules for the first 3-5 months after an initial infection is found can be a good compromise. After some months, the virus may be so widely spread that prevention levels might be lowered, depending on the balance between cost and risk a company wants to take.

Separating the first infection spots is certainly useful at the beginning. One hypothesis is that the virus moves 2-4 rows away from the initial infection (hotspot) every week if no hygiene measures are taken. Extra hygiene in those rows and working in this area by dedicated people and, at the end of the day, slows down the spread.

The experience is also that a first hotspot is often followed by other spots some weeks later. Because the virus has probably moved from the first hotspot to other locations before it was visible. Separating the first hotspot can also reduce the number of secondary spots.

In case of a late infection (e.g., 6 months after planting and in summer), we have seen that removing the hotspot by removing plants in the adhering 3-6 rows can 'stop' the infection from spreading. This removal of plants feels very rigorous, but the spread is stopped because there are no plants anymore, and workers are not going into those rows and are not contaminated. This also reduces the risk of secondary spreading. In older crops, the balance between destroying or extra hygiene can be in favor of destroying some rows.

Separated blocks

A good basic measure is to divide a greenhouse into blocks with separate people and equipment for each block. Reducing the number of crossing lines between blocks also reduces the spread of the virus all over the site. The size of these blocks depends on your company and can be based on the way the greenhouse is built for example, if the greenhouse is square, 4 blocks may be ideal. In many cases, the people and harvested fruits are still moving over the same main path or corridor, which is not optimal but does reduce the exchange of viruses.

If possible, trolleys and harvesting crates should also be dedicated to a certain block. This way of working is not easy, and the optimal size of a block seems to be between 1 and 5 hectares. The idea of blocks can be useful not only for virus control, but also to treat only affected parts of the site with other pests or diseases.

A ToBRFV infection can easily happen, and taking precautions and being prepared is the first step to take measures that are working and reasonable. A risk assessment and making people aware support this approach. In general, the later an infection starts and the less the virus is spread, the better it is for the plants and for the final yield.

For more information:

Bayer

www.bayer.com