"Vertically farming vanilla in a climate-controlled environment is possible in all regions of the world. It just won't be as profitable everywhere, given the difference in energy needs and cost. Dry and sunny countries are best suited because it's easier to lower the temperature in the greenhouse, if necessary. And you need some sunlight even for our deep-shade cultivation protocol. Creating high humidity in enclosed greenhouses is relatively easy, regardless of where you are in the world," affirms Oren Zilbermann, CEO and co-founder of Israeli agrotech company Vanilla Vida.

Vanilla orchids thrive in jungles near the equator. They grow in Cameroon, Uganda, Peru, Mexico, and Indonesia. Although a little further south, Madagascar has the same climate. In fact, 60-70% of the world's natural vanilla is produced on that island.

"However, outdoor cultivation in the tropics has faced some issues recently, the most problematic being climate change. Hurricanes and cyclones increasingly ravage Madagascar. In 2017, the island lost half of its production, and Ever since then, prices have increased fivefold to between $600 and $700/kg," he adds.

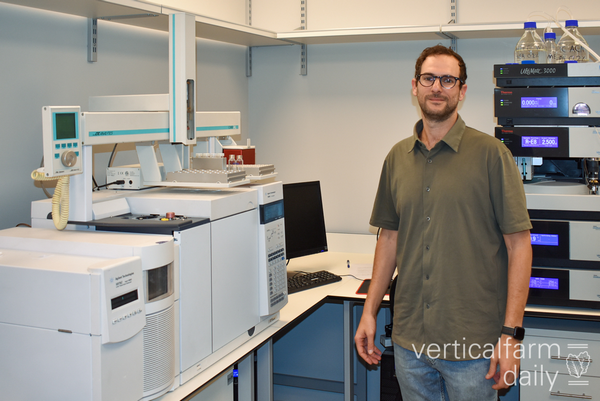

Oren Zilbermann at their production facility in Israel

Of the vanilla on the market, 80% is synthetic

According to Oren, the biggest challenge, however, lies with demand. The aromatics and perfume industry, the sector's primary customer, wants the natural product - which represents only five percent of the global vanilla supply - to have stable supply, quality, and price. Eighty percent of that supply is of synthetic origin; the remaining 15% is derived from natural vanillin molecules created in bioreactors. That process is cheaper than growing the beans but much more expensive than manufacturing the synthetic variety.

"We're a vertically integrated company: managing cultivation, processing, and marketing from A to Z. We control everything, from tissue culture and seedlings to the drying process and distribution. We rely on venture capital investors, like the Strauss Group, one of the largest food producers in Israel, as well as several joint ventures. So our know-how and focus aren't exclusively on cultivation. We're an agrotech and food tech company in one," Oren explains.

Vanilla Vida has multiple cultivation sites with climate-controlled greenhouses in Israel and is expanding to North America. "We're not the only ones growing vanilla this way. There's competition, but we'll be the market leader within 18 months. That's because our cultivation concept differs from what the research institutions propose - we focus on deep shade - and our business concept, too, is different from that of competitors."

Unprocessed beans when they arrive at Vanilla Vida

Two commercial varieties

Vanilla Vida cultivates the vanilla variety, planifolia Andrews. The American Food and Drug Administration also regards vanilla tahitensis Moore as food-safe. The latter represents only five percent of the market; it has a far lower vanillin concentration, and its aroma and flavor are also less popular. All sectors, from the food industry to cosmetics and pharmaceuticals, prefer vanilla planifolia.

Besides growing its own vanilla, this Israeli company also imports the product from numerous countries of origin, drying that in its facilities. Processing imported product is less profitable, but, says Oren, it helps enter the market more quickly and efficiently. A crop cycle often takes longer. In nature, it takes three years for the plant to first flower. In a climate-controlled greenhouse, where you create the correct temperature, light, and humidity conditions, the first buds appear after 'only' 18 months.

The controlled greenhouse

Open-field cultivation is unstable

"In Madagascar, as in most cultivation countries, the plants only bloom once a year. Globally, most harvesting is from June to August. Only in Uganda and Papua New Guinea do these plants flower twice a year. Even so, the second flowering, which falls in December, is shorter, and the product's quality's usually lower. Customers who couldn't get a sufficient supply of adequate quality during those few months have to wait a year for the new crop."

"Climate-controlled facilities can, however, be divided into multiple cultivation spaces. That allows for year-round flowering, which meets clients' main demands: stable supply, quality, and price. Plus, a cultivation company with regular production can hire permanent staff, so they don't have to rely on seasonal workers for a short harvest period. Shortage of hands is a big problem in horticulture these days," Oren continues.

Deep shade

Vanilla Vida uses solar panels to create a deep shade for the plants as solar panels cover 80% of the roofs of the greenhouses to imitate the jungle canopy. Besides that, solar energy helps to spread business risks through low-cost loans as part of the energy transition. The company can now set up a dual-function structure, which includes cheap energy and deep shade for their main business: growing vanilla. Energy costs in Israel have risen only about 15%-30% in the past year - peanuts, compared to Europe - because Israel has offshore gas fields.

He says they precisely control pollination in their enclosed greenhouse spaces. "That's still done manually, but we hope to make a technological method world-famous within 18 months. Our trellis system, too, is fairly unique. It protects the orchids from one of the biggest dangers to cultivation: Fusarium Oxysporum, a fungus against which there are, as yet, no effective remedies."

Huge gulf between supply and demand

Oren does not believe the high-tech character of greenhouse vanilla cultivation will not threaten African growers' livelihood. "There's too much demand. There's currently about a 40% gap between supply and demand, which traditional growing will never close. But, neither can CEA immediately. In the current context of climate change, open-field cultivation's too volatile."

Vanilla orchids are far more sensitive than any fruit or vegetable. By introducing technology and thus improved quality and a stable supply to an inherently non-technological market, the company further increases the natural product's overall demand. Vanilla Vida, therefore, advises their grower-suppliers in other countries about cultivation methods too. That lets them harvest higher-quality vanilla and gives them higher-quality beans to import.

Sugar crystals are clearly visible after the drying process

How important is the drying process?

Even though natural vanilla only accounts for five percent of the total market, the flavor and fragrance market's demand for it has climbed sharply in recent years. Each customer has specific requirements regarding the vanilla's properties and quality. For example, the cosmetics, patisserie, and chocolate sectors have different needs.

"Our sophisticated drying and processing system can meet those. Compare it to coffee. There, the roasting process determines the final flavor profile. There are various vital parameters like light, humidity, and temperature. Don't forget that the drying process takes three months; that would be four to five, traditionally. The pods' inner metabolism is active for 90 days, which you have to respond to with the correct environmental conditions," Oren explains.

Vanilla Vida uses wholly data-driven methods to convert glycovanillin to vanillin. "Naturally, we use enzymes to activate certain flavors and obtain different aromas. We know our own-grown beans' aroma and flavor potential well. With the imported product, we first analyze the raw material's metabolism to determine which way to best use it," Oren explains.

Hands-on quality checks

Tripling the aromatic substance

In traditional cultivation and drying, the vanilla usually constitutes 1.6% of the content. Vanilla Vida, however, manages to boost that to between two and four percent. It is now using an innovative technique to reach five to six percent. "If we can offer buyers something with a much stronger aroma, they'll need less and can thus save on the cost price."

"Madagascan vanilla costs $250/kg, regardless of its vanillin concentration. The local government regulates those prices. For vanilla from, say, Uganda, Peru, or Mexico, market laws apply. Currently, that with a low concentration of vanillin (1-1.5%) fetches at most $130 per kilogram. For the better product, growers get $200. In contrast, our vanilla's selling price is determined per gram of vanillin. Customers are, thus, sure of the quality, and with a guaranteed vanillin percentage, cost prices end up being on average 20% lower than that from open-field cultivation."

It takes a lot of work not only to grow but also and especially, to dry vanilla. "It took us 18 months to design, via machine learning, an optical and image sorting system. After all, there was hardly any data on vanilla," says Oren, who also explains that their production process produces no waste. "We use everything, for instance, sending the inferior quality material to a candle manufacturer in California," he concludes.

Vanilla Vida's tissue culture is done through a joint venture, propagation at a cultivation site in northern Israel, and drying and processing at the production site in Or Yehuda. The company supplies large flavor and fragrance market players with vanilla, as well as distributors who supply the product to chefs, patisseries, and ice cream parlors in Europe and the U.S. The company is ISO and ASAP certified and is now pursuing organic and Fairtrade certification, the latter for its imported product from Africa.

For more information:

Oren Zilbermann, CEO

Vanilla Vida

oren@vanillavida.com

Gali@vanillavida.com

www.vanillavida.com