New techniques for growing food would produce fresh vegetables in dense urban areas while leaving a lighter carbon footprint and using less water, energy, and land than traditional farming methods, according to researchers from Clemson University and South Korea's Gyeongsang National University.

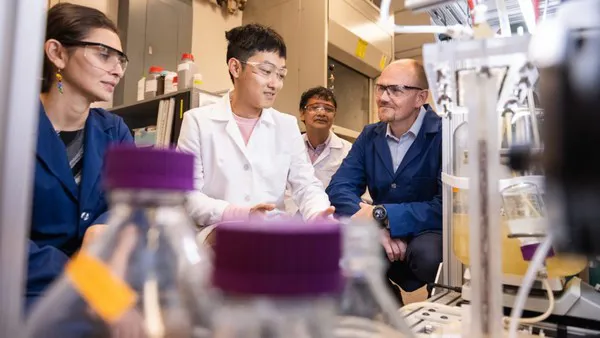

The project brings together researchers from the two universities and is funded with $1.5 million from a National Science Foundation program called Partnerships for International Research and Education (PIRE).

The system researchers are developing would use an anaerobic membrane bioreactor to filter harmful contaminants out of wastewater while leaving behind nutrients that fertilize plants. The treated water would be used on crops, such as lettuce, that are growing in an indoor, soil-free hydroponic system that is engineered to efficiently use the water and its nutrients.

Treating wastewater would produce methane that could be converted to carbon dioxide. The carbon dioxide would enhance plant growth by enriching the air inside a greenhouse or modular container that has been reconfigured for growing crops.

The idea is to grow vegetables where they are most needed without having to ship them from hundreds or even thousands of miles away. Researchers aim to design a system that would benefit any urban or suburban community, and they see particularly high promise for application in impoverished cities and disaster zones.

The system is similar to one proposed by NASA in the 1990s as a way of growing crops to support planet colonization, researchers said.

The principal investigator on the project is David Ladner, associate professor of environmental engineering and Earth sciences at Clemson. Ladner said the project brings together his research interests in wastewater and water for human consumption.

"I like the collaborative nature and international aspect of this project," he said. "We have a lot to learn from our partners in South Korea, and hopefully, we can export some of our knowledge and ideas from the United States to other parts of the world."

Byoung Ryong Jeong, professor of horticulture at Gyeongsang National University, said it is a pleasure to be a part of the project, especially since it is an international collaboration to reduce carbon emissions and use water more efficiently.

"These are not local issues occurring in specific regions of the world, but indeed are global," Jeong said. "As a horticulturist, I am very excited to work with Clemson engineers who are trying to use water and energy from our living environment to shape the future of horticulture. Our team is well positioned to yield a fruitful harvest in finding not only practical solutions for the reuse of wastewater and other available resources but also to produce fresh, healthy crops."

Among the collaborators on the project is Diana Vanegas, an assistant professor of environmental engineering and Earth sciences at Clemson.

"This is a project aimed at tackling the single most important problem that humanity is facing right now, which is climate change," she said. "I'm excited about the East-West academic collaboration with South Korea and the United States. These global problems have to be solved with a global partnership, and international relations are very useful for that."

Water conservation

David Flynn, the general manager of AmplifiedAg, said the company is excited to partner with Clemson.

"Water conservation is strategically important to us, the indoor agriculture community, and the world overall," he said. "Our method of growing hydroponically is very efficient in terms of water usage, but we want to drive that consumption down even further. Our data-driven technology is currently being used extensively in indoor agriculture research, and we believe it will greatly assist Clemson in its endeavor to repurpose wastewater for farming of all types."

The project could have a widespread impact, said a collaborator, Raghupathy Karthikeyan, the Charles Carter Newman Endowed Chair of Natural Resources Engineering in Clemson's Department of Agricultural Sciences.

"We see food deserts, and urban farming is coming up quite a bit as a solution, not only in the U.S. but in developing countries where they have water issues," Karthikeyan said. "As a result of this research, we could tap into water that is treated using an anaerobic membrane to grow food and help those most in need to become more self-sufficient. This system would be a way to get sustainable food production in urban clusters."

Also among the collaborators is Gary Amy, a Dean's Distinguished Professor of environmental engineering and Earth sciences.

"In an era of increasing resource scarcity which includes food, water, arable land, and fertilizers, we are in need of a new paradigm for sustainable agriculture: the integration of non-traditional waters for irrigation, high-intensity crop cultivation, and new sources of fertilizers, all of which are addressed in our project," Amy said. "Of particular importance is the convergence of Korean expertise in controlled environment agriculture and U.S. expertise on wastewater reclamation by anaerobic membrane bioreactor technology."

Nature's balance

Another collaborator is Jeffrey Adelberg, a professor of horticulture at Clemson. "In our project, we put nature's balance back into vegetable production," he said. "Animals excrete the building blocks plants use to build the high energy molecules we use as food. Our waste products degrade to water, ammonium, carbon dioxide and methane, and some mineral nutrients. All have value when isolated from the problematic bacteria in our waste stream. NASA envisioned this as a closed system for food production and waste recycling back in the 1990s as part of planetary colonization. Now its Earth-based analog will get a practical update."

Jesus M. de la Garza, director of Clemson's School of Civil and Environmental Engineering and Earth Sciences, said Clemson is well suited to lead the project.

"David Ladner's background in sustainable water treatment processes uniquely positions him to serve as principal investigator on this research," de la Garza said. "He has built a multidisciplinary, international team that sets the stage for great success."

The grant is the first Clemson has received as part of the PIRE program.

Anand Gramopadhye, dean of the College of Engineering, Computing, and Applied Sciences, said it is well deserved.

"Dr. Ladner and his team have proposed an innovative solution to food security issues and wastewater treatment," Gramopadhye said. "Their interdisciplinary partnership is aimed at creating sustainable, real-world solutions to urgent global needs. I offer David and his team my wholehearted congratulations on the grant."

For more information:

Clemson University

www.clemson.edu