To avoid salt in the soil, plants can change their root direction and grow away from saline areas. University of Copenhagen researchers helped find out what makes this possible. The discovery changes our understanding of how plants change their shape and direction of growth and may help alleviate the accelerating global problem of high soil salinity on farmland.

"The world needs crops that can better withstand salt. If we are to develop plants that are more salt-tolerant, it is important to first understand the mechanisms by which they react to salt," explains Professor Staffan Persson of the University of Copenhagen's Department of Plant and Environmental Sciences. He continues:

"To avoid salt in the soil, plants can make their roots grow away from saline areas. It is a vital mechanism. Until now, it is unclear how they do this."

Together with a group of foreign research colleagues, Persson discovered exactly what happens inside plants at a cellular and molecular level as their roots grow away from salt. The results have been published in the scientific journal Developmental Cell.

Seedlings in media without and with salt (credit: Bo Yu)

Stress hormones come into play

The research group has discovered that when a plant senses local concentrations of salt, the stress hormone ABA (abscisic acid) is activated in the plant. This hormone then sets a response mechanism into motion.

"The plant has a stress hormone triggered by salt. This hormone causes a reorganization of the tiny protein-based tubes in the cell called the cytoskeleton. The reorganization then causes the cellulose fibers surrounding the root cells to make a similar rearrangement, forcing the root to twist in such a way that it grows away from the salt," explains Professor Persson.

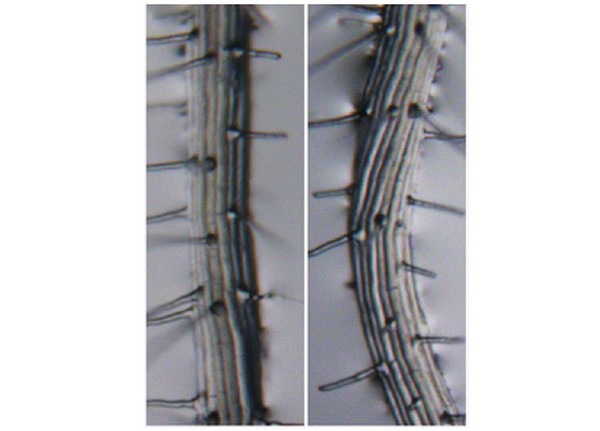

Microscopic images of roots (credit: Bo Yu)

Changes the understanding of how plants change shape

The leading role played by the stress hormone is what makes the discovery a surprise for the researchers. Until now, it was believed that the hormone auxin controlled a plant's ability to change directions in response to various environmental influences (known as tropisms).

"That the stress hormone ABA is crucial for plants being able to reorganize their cell walls and change shape and direction of growth is completely new. This could open new avenues in plant research, where there will be a greater focus on the significant role that the hormone seems to play in the ability of plants to cope with various conditions by changing movement," says Staffan Persson.

By mutating a single amino acid in a protein that drives the twisting of the root, the researchers were able to reverse the twist so that the plant could not grow away from the salt.

Persson believes that it will be some time before the new knowledge is applied in agriculture – not least because GMOs remain banned in the EU. However, the results may open the way for the development of more salt-tolerant crop varieties.

"Plants produce more of the stress hormone when they sense salt. It's not hard to imagine that if you can speed up a plant's stress response by changing other aspects of the cytoskeleton, you can probably make its root-twist happen faster. In this way, we can strengthen plants by reducing their exposure to salt," says Professor Persson.

For more information:

University of Copenhagen

Professor Staffan Persson

[email protected]

www.news.ku.dk