Finland has the highest average tomato and cucumber consumption of all Northern European countries. Finns eat an average of 12.1kg of tomatoes and 10.2kg of cucumbers per year. Both are about double that of Norway. And remarkably, 60% of those tomatoes and no less than 93% of the cucumbers eaten in Finland come from local greenhouses.

We visited the Finnish Greenhouse Growers Association, which, in 2017, celebrated its 100th anniversary. This trade organization collects and publishes data on greenhouse farming, advises its 300 members, and lobbies for the sector with policymakers. It also does marketing campaigns for greenhouse-grown vegetables, soft fruit, herbs, and ornamental plants. Plus, it publishes the trade journal 'Puutarha&kauppa' - with information on greenhouse as well as outdoor cultivation - and organizes the annual LEPAA trade fair in August, attended by some 200 exhibitors. All this makes it the perfect partner to talk to about greenhouse cultivation in the far North of Europe.

Tomatoes, cucumber, lettuce, and herbs

It is not an oversight that this article only referred to tomatoes and cucumbers in its first paragraph. The figures quoted are downright impressive. However, other greenhouse vegetable stats are diametrically opposite. Finnish growers cultivate tomatoes on a roughly 97-hectare area and cucumbers on 53 hectares. Bell peppers, though, have to make do with nine hectares, and there are zero eggplants or zucchini being grown, at least commercially, in greenhouses.

Statistics from LUKE institute

EU Grants

"It all has to do with tomatoes and cucumbers receiving EU grants, while neither eggplants nor zucchini do," says Niina Kangas, the Finnish Greenhouse Growers Association CEO. "But as those subsidies continue to shrink, we expect growers to free up space for other greenhouse vegetables. Some growers are even beginning to cultivate green beans." Lassi Remes, this umbrella organization's cultivation specialist, adds that although some farmers are already focusing on bell peppers, it is still hard to compete with the imported product's prices.

There are subsidies for other products besides tomatoes and cucumbers - lettuce, good for 21 hectares of greenhouse space, and herbs, like parsley and dill, grown on 12 and eight hectares, respectively. For its 5.5 million inhabitants, Finnish herb and lettuce cultivation are effectively self-sufficient. Some carrots, onions, potatoes, and cabbage are also grown in greenhouses. But none on more than five hectares in total. On the other hand, soft fruit farming is on the rise, with more than six hectares for strawberries and 1.5 hectares for other berries, mainly raspberries, already.

Small-scale farming

Finland boasts 838 greenhouse companies, half of which cultivate vegetables, herbs, and soft fruit, the other half ornamental plants. More than two-thirds of the approximately 375 hectares are devoted to fruit and vegetables. There are only a handful of large farms. The smallest is 300m2, the largest, about 12 hectares. The average acreage per farm is less than half a hectare.

Yet, there is a growing trend toward fewer businesses, proven by the fact that, in 2016, there were still almost 1,200 active greenhouse farmers. "And that trend will only continue because, given that the greenhouses are generally older, it's often difficult to find successors if you don't have one within the family," explains Niina, who before becoming CEO in January had been the association's Plant Health Advisor for a decade. There are hardly any new companies being founded, especially now that production costs have risen by 20-30%. The slightly higher sales prices do not nearly make up for that.

Picture by Kauppapuutarhaliitto ry

Picture by Kauppapuutarhaliitto ry

Stable greenhouse acreage

In Finland, greenhouse acreage has been fairly stable for years. While some companies scale up, it is always limited. That's because, given tomatoes and cucumbers' current market share, and the fact that Finland does not export any greenhouse vegetables, there is little room for cultivation expansion. At certain times of the year, there is even overproduction. "Then prices inevitably drop, although Finnish greenhouse cultivation is generally profitable." Because the sector is so small and the market limited, investment companies have not yet developed a keen interest in Finnish greenhouse cultivation, unlike in countries like Spain and the Netherlands. "But developments usually take five years to reach us, so it's still possible," says Lassi.

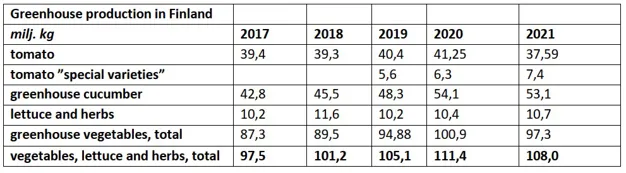

Last year, the entire Finnish greenhouse sector was valued at €410 million, of which vegetables and herbs were good for €306 million, soft fruit, €4 million, and ornamental plants, €100 million. The country's greenhouses produced 37.59 million kg of standard tomatoes, of which 7.4 million kg of tomato specialties, 53.1 million kilograms of cucumbers, and 10.7 million kg of lettuce and herbs.

Specialty imports

The association maintains good relations with the three largest retail players in the country, Inex, Kesko, and Lidl. Finnish consumers also prefer local products. These factors explain why so many tomatoes and cucumbers are supplied to the local market. "Of course, because price still prevails, there's still room for import products," says Niina. "Ask a Finn which vegetables they prefer, and they'll invariably say local and then sustainably grown products. But when it comes down to it, price is often the deciding factor."

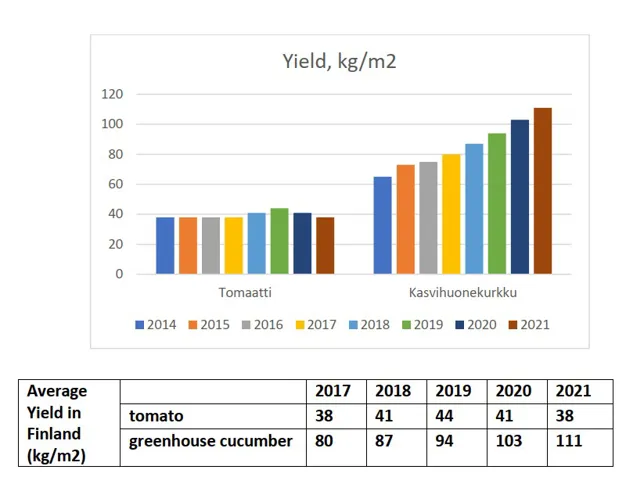

"In the fall, our tomatoes cannot compete in price with their cheaper Polish counterparts. Spanish and Dutch tomatoes are available year-round. Finnish specialty cultivation, in particular, isn't yet fully developed, although this is gradually changing. For example, tomatoes' average yields have dropped from 44 kg/m2 in 2019 to 38 kg/m2. That isn't because of poorer cultivation practices, but due to an expansion of the area under specialty crops."

Standard round tomatoes can yield between 80 and 100 kg/m2, with cucumbers averaging 102 111 kg/m2. "But, the top growers harvest up to 200 kg of cucumber per square meter," says Lassi, who says Finland does not have any breeders. The country imports all its seeds, and growers test them to see which varieties perform best in their greenhouses. The Dutch company, Rijk Zwaan and De Ruiter Enza Zaden, is listed as the largest tomato segment seed supplier.

Picture by Kauppapuutarhaliitto ry

Picture by Kauppapuutarhaliitto ry

Local trumps organic

Finland's organic acreage, too, has been stable for decades. For people whose shopping habits include considering the environment, locally-grown currently surpasses organic cultivation, the team says. The reasoning is, thus, 'why get organic vegetables from afar when local products are available, especially if they're grown, almost chemically-free, in greenhouses.' "Everyone's also still closely considering the situation, given the new EU standards for organic cultivation," explains Lassi. "Organic farming might be entirely chemical-free, yet new EU regulations demand root connection to the soil, with some exception, but at the moment, it is possible to grow without soil connection in growing media."

"No one wants to invest in expanding the production method at the moment. The situation's still too uncertain. We've used the same philosophy and protocols for organic cultivation for years. So, it will take the sector time to adapt to the new regulations. In any case, environmentally-wise, greenhouse cultivation has a good image because it uses integrated crop protection strategies and very few chemicals."

Picture by Kauppapuutarhaliitto ry

Picture by Kauppapuutarhaliitto ry

Using wood for heating and grid power for lighting

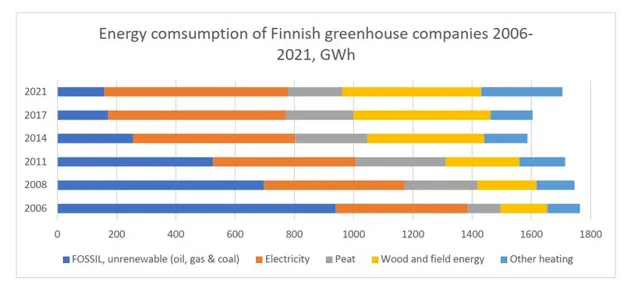

Finnish greenhouses are heated using primarily wood chips and pellets. "Finland has a huge timber industry, which, of course, benefits the greenhouse sector. And the wood chips are usually fed into the burners automatically, so you need no additional workers for that. Some growers also burn peat, another typical Finnish raw material. We use very little gas. Wood and peat are cheaper. For lighting, the growers use electricity from the national grid, which allows them tax benefits. Nuclear power plants and windmills generate most of Finland's power. But 15 years ago, things looked completely different; half of the heating and lighting was still petroleum, natural gas, and coal-dependent. These days, those fossil fuels have less than 10% share," continues Niina.

Statistics from the LUKE institute

She is aware of only one grower who was deterred from planting this winter by the high electricity prices. "Most have long-term power contracts and therefore aren't subject to the volatile prices. Wood for heating is relatively inexpensive, and while it may be cold in the winter, Finnish skies are usually open and blue. However, if energy prices remain high, several growers will undoubtedly, struggle. But some would have reached retirement age in a few years and stopped anyway. There are, however, some growers who are using less lighting. And although that produces less yield, it makes for higher market prices."

The association reckons that, between 2004 and 2017, the Finnish greenhouse sector's carbon footprint shrank by 56%. "Five years ago, tomatoes had a carbon footprint of 2.6kg/kg of product; for cucumbers, it was 2kg, and for lettuce, 2.7kg. That's still higher than in Spain, but our best growers are already achieving levels lower than the Spanish average," Lassi says.

Challenges: labor and peat

As in other countries, increasing production costs are causing Finnish greenhouse growers headaches too. "In the short term, production costs are the biggest issue, especially for small growers. In the long term, I see labor availability and, as mentioned earlier, the succession within growing companies becoming problems. But for now, labor issues aren't such that farmers are considering full automation. It costs far too much for our small-scale companies to invest in, say, greenhouse robots. Packaging facilities are, however, becoming increasingly automated."

But European policy could pose the biggest threat. "We surveyed our members two years ago," explains Niina, "and 90% said they'd stop if peat was banned as a growing medium. It's currently the most important growing medium in Finland, where growers rarely use coconut substrate. But peat's future is hanging by a thread: its cutting and classification as a product could be banned. Using it could lead to companies not being allowed access to grants. We hope policymakers understand that it, not coconut, is a local product for Finland and Europe. And that it's an important growing medium for the entire European cultivation sector."

Picture by Kauppapuutarhaliitto ry

Made in Finland

The peat issue aside, Finnish greenhouse horticulture's future generally looks bright, not least because of Finnish consumers' choice of locally-grown products. "And we're eagerly responding to that. We're fully committed to marketing all Finnish greenhouse products. We have a quality mark and logo, and can even say we've greatly contributed to that good demand for local products. We've been promoting 100% Finnish products since the 1980s. By the way, the growers finance the marketing campaign. They contribute as much as their respective production levels allow. We get no government assistance for that; we see to it ourselves. We're active on places like social media and advertise in the written media. Ninety percent of Finns recognize our logo," Niina concludes.

For more information:

Niina Kangas

Kauppapuutarhaliitto ry | Puutarha&kauppa

www.kauppapuutarhaliitto.fi/

www.puutarhakauppa.fi/