In the fall of 2004, researchers on a soybean farm near Baton Rouge, Louisiana, were surprised to discover a multitude of soybean plants on which leaves had developed reddish-brown lesions.

The culprit soon was identified as Asian soybean rust, an aggressive and destructive disease of soybean that had not been seen on the continent before. The U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service immediately deployed a rapid response team to search southern states for other infected host plants.

First recorded in Japan in 1902, Asian soybean rust spores had been blown from Asia to Australia and Africa before arriving in South America in 2000. Previously, the causal pathogen had been stockpiled as a biological weapon, and North America was the only major soybean-producing region worldwide that was rust-free.

Concerned about the source of the pathogen and its potential to spread in the U.S., the USDA and soybean growers needed a plant pathology “gumshoe” on the case.

Predictive map

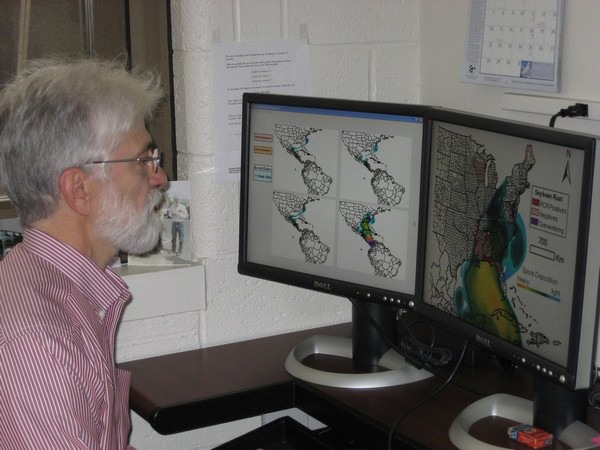

They turned to Scott Isard, an aerobiologist in Penn State’s College of Agricultural Sciences. An expert in the long-distance aerial movement of animal and plant life, Isard then was leading a USDA-funded study on soybean rust movement in South America.

Isard provided the USDA with a predictive map of spore deposition that proved useful in the early days of the search. Next, he and his team set up an internet-based monitoring and modeling system to predict the aerial movement and deposition of the pathogen into soybean fields through the U.S., Canada and Mexico. Their efforts eventually became known as the Integrated Pest Information Platform for Extension and Education Cooperative Agricultural Project or iPiPE.

“Most administrators in the USDA did not think we could set up a system that involved so many states and provide useful information for making soybean rust management decisions,” Isard said. “Extension specialists from around the nation and growers helped build the system. It was the unprecedented support from the growers, extension specialists, industry and USDA agencies that made it work.”

And it worked well. USDA calculations showed that the iPiPE saved soybean growers as much as $200 million in 2005 alone. Fungicide use in the U.S. potentially could have doubled in 2005 over 2004 if the USDA had not adopted the platform, noted Isard. For their work, the soybean rust team received the U.S. Secretary of Agriculture Group Honor Award for Excellence.

Pest biology

The platform since has expanded to include insects, other pathogens and beneficial organisms that impact a variety of crops that U.S. farmers grow. It incorporates National Weather Service data, field reports from extension specialists and growers nationwide, and knowledge of pest biology. This information can help growers monitor and anticipate pest problems and take appropriate action before crops are damaged, often while reducing the need for pesticides.

Continued funding from USDA’s National Institute of Food and Agriculture’s Competitive Grant Program — and a growing stakeholder and disease-monitoring portfolio — affirm the platform’s value to agriculture.

“In each of the five years of the $7 million USDA-NIFA grant, we issued a call for proposals to extension specialists who were interested in working with stakeholders and mentoring undergraduate students,” said Isard. “And each year, we added seven news crops to our monitoring profile, from sweet corn in Pennsylvania to cotton in California and crops in places in between.”

Internship program

The project’s impact goes beyond helping producers manage insects, diseases, and beneficial organisms, Isard pointed out, as nearly 100 undergraduate students in 22 states have gained experience through the iPiPE internship program.

The students created extension literature on target pests, received education in pest diagnostics and food-security concepts, collected pest observations in the field, and interacted with extension professionals and stakeholders at grower meetings.

Exit surveys of the interns found that almost all believed the iPiPE internship was a helpful path to achieving their ambitions. “They liked the many activities, they learned a lot about extension, and many of them now have jobs in agriculture,” Isard said.

Database

With an eye on the future — and with Isard’s impending retirement this summer — the iPiPE platform was incorporated into the University of Georgia’s EDDMapS Integrated Pest Management system in 2020. The coupling of these platform powerhouses will provide sustainability and increase participation in pest and disease monitoring, noted Isard.

“The combined database contains more than 1.5 million observations on more than 800 crop-pest species,” he said. “The goal all along has been to convince agricultural stakeholders that there is value to themselves and others in sharing observations of pests in their fields, and I hope it will continue to accelerate. This effort to create a culture of sharing important information is what I consider the highlight of my career.”

Carolee Bull, professor and head of the Department of Plant Pathology and Environmental Microbiology at Penn State, commended Isard for a career dedicated to sustainable agriculture.

“His efforts have raised the benchmarks for projects in all three areas of the land-grant mission,” she said. “This work will have long-lasting impact on applied, collaborative and participatory research, on education and models for involving undergraduates in authentic research, and on extension of knowledge to stakeholders.”