Plants can perceive and react to light across a wide spectrum. New research from Prof. Nitzan Shabek’s laboratory in the Department of Plant Biology, College of Biological Sciences shows how plants can respond to blue light in particular.

“Plants can see much better than we can,” Shabek said.

Plants don’t have dedicated light-detecting organs, like our eyes. They do have a variety of dedicated receptors that can sense almost every single wavelength. One such are the blue light photoreceptors called cryptochromes. When the cryptochrome detects an incoming photon, it reacts in a way that triggers a unique physiological response.

Cryptochromes probably appeared billions of years ago with the first living bacteria and they are very similar across bacteria, plants and animals. We have cryptochromes in our own eyes, where they are involved in maintaining our circadian clock. In plants, cryptochromes govern a variety of critical processes including seed germination, flowering time and entrainment of the circadian clock. However, the photochemistry, regulation, and light-induced structural changes remain unclear.

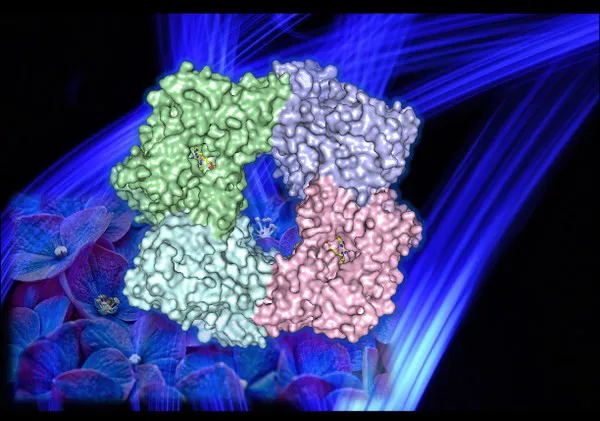

In a new study, published Jan. 4 in Nature Communications Biology, Shabek’s lab determined the crystal structure of part of the blue-light receptor, cryptochrome-2, in the model plant Arabidopsis thaliana. They found that the light-detecting part of the molecule changes its structure when it reacts with light particles, going from a single unit to a structure made of four units linked together, or tetramer.

Rearrangement leads to gene activation

“This rearrangement process, called photo-induced oligomerization, is also very intriguing because certain elements within the protein undergo changes when exposed to blue light. Our molecular structure suggests that these light-induced changes release transcriptional regulators that control expression of specific genes in plants,” Shabek said.

The researchers were able to work out the structure of cryptochrome-2 with the aid of the Advanced Light Source X-ray facility at the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory.

The Shabek lab broadly studies how plants sense their environment from the molecular to the organismal levels.

“This work is part of our long-term goals to understand sensing mechanisms in plants. We are interested in hormone perceptions as well as light signaling pathways,” Shabek said.

The team first solved the crystal structure of the blue light receptor two years ago, using X-ray crystallography and biochemical approaches. With recent advances in plant sciences and structural biology, they were able to update the model and reveal the missing piece of the puzzle.