Greenhouse automation has come a long way in the past two decades. Give it another two decades, and it may completely overshadow the human element in the greenhouse. At least, that's a conclusion you might draw when looking at the results of the Autonomous Greenhouse Challenge and the implications of it in horticultural practice. In a webinar hosted by one of the challenge's sponsors, Heliospectra, AI was discussed from three different perspectives: academia, tech suppliers, and the grower.

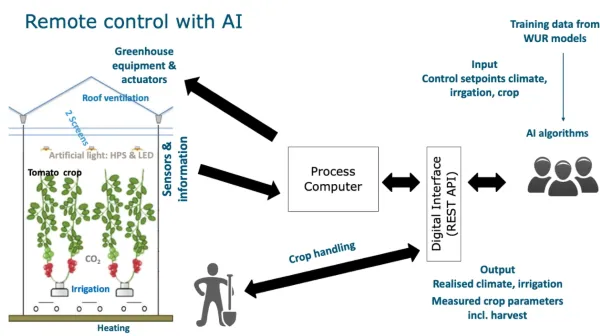

Kicking off the webinar, Silke Hemming, head of the scientific research team Greenhouse Technology within Wageningen University & Research, shared some insights provided by the challenge. The idea was to have decisions made autonomously by the AI system that would normally be made by the grower. This can range from adjusting the climate computer to the choice of when to produce what, and what resources to use accordingly. To achieve this, the teams had to make algorithms to automatically decide on set points for climate and irrigation. Next to that teams had also remotely to decide on crop management such as stem density, leaf picking, and fruit pruning.

The optimal strategy

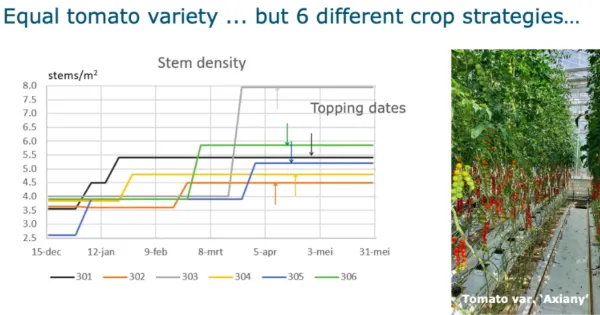

The participating teams used different strategies to achieve the goal of growing the best tomatoes as sustainably as possible. Most of them, for instance, increased stem density at some point in the season - the reference growers even doubled the stem density; the winning team, Automatoes, also increased the stem density during the competition.

For more results from the challenge, please also refer to this article.

Lessons learned

Silke then shared some of the take home messages the challenge has yielded. It turns out that crop management is key when you're going for a combination of high quality production and a high net profit. Another takeaway is that if you want to apply these modern technologies, you need objective data on all aspects of the cultivation, otherwise you can't develop the necessary algorithms. And finally, humans aren't going away completely any time soon - they're still needed to perform crop handling, until those tasks can also be taken over by robots.

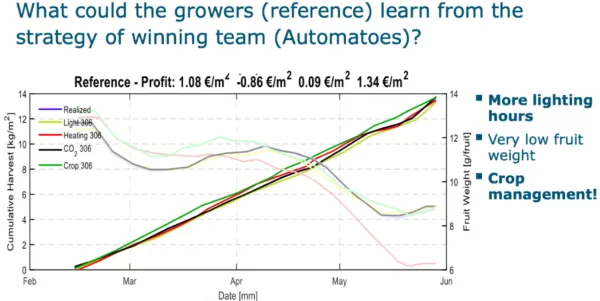

At the end of Silke's presentation, she also took a look at what the team of reference growers could have done better. "We used our 'fancy' models," she says, "and analyzed if the growers would have applied part of the Automatoes strategy, would they have achieved a better result?" It turns out that if the reference growers would have used the lighting strategy of team Automatoes, they would have achieved better resource use. And using the cropping strategy from Automatoes, they'd have reached a higher net profit and even a much higher production. So while AI won't completely replace human growers in the near future, we can already learn a thing or two from the machines.

Greenhouse builders become full service suppliers

Next up was Leonard Baart de la Faille, team captain of the challenge's winning team, Automatoes. Having a decade of greenhouse research experience under his belt, Leonard recently joined Van der Hoeven Horticultural Projects as R&D engineer. "At Van der Hoeven, we design and build greenhouses, and we see a very important trend: many years ago it was only about building a construction, but now we're a full service turnkey greenhouse supplier. We help the growers in starting up and training, sometimes bringing in a grower, like a team mate who's currently starting a greenhouse in Kazakhstan. Investors are looking for full service: they don't just want a greenhouse, they want a greenhouse with a well-performing crop in it."

Participating in the challenge was a perfect way to put that full-service philosophy to the test. Leonard explains how his team tackled the challenge. "We started out by putting the plant central. After all, you can only do well if you let the plant perform optimally, so you design the whole system around the greenhouse. If you do that, you don't just achieve good production, you also do it efficiently.

Plant balance

Leonard and his team followed the Plant Empowerment strategy, keeping the plant in balance. "We didn't mimic a grower using a lot of data from other greenhouses, we tried using the data from this greenhouse only." The biggest challenge then is to objectify and quantify what the grower is trying to achieve. "If you bring it back to a number, then you can do something with that. Next, we broke it down into pieces, choosing separate AI for each of those blocks." Next, Leonard gave some examples of these 'AI puzzle pieces'.

"One really simple example is irrigation. We looked at the sensors in the slabs and discussed this with our grower. We were trying to achieve a certain drydown, to steer the crop in the long term balance. The moment when you stop irrigating in the afternoon makes for a certain level in the morning when you start up again. With a simple regression model, we were able to fairly simply calculate the right stopping time."

A more complicated aspect was ventilation. Leonard calls it "probably the most important part to control in a greenhouse, but also the most tricky part". In the challenge, they didn't use the conventional P-band control, because "then you tend to ventilate too much. You want high radiation, high CO2 and a high temperature, but also not too low humidity, or the stomata might close. So, we used a model that calculated stomata behavior to determine how much to ventilate."

A final example showcasing how team Automatoes put plant balance center stage, is the use of the 24-hour temperature in steering the plant. "On a daily timescale, radiation should be in balance with the 24-hour temperature. Based on the weather forecast, we made a climate plan, keeping a ratio between temperature and light, then we look at what the plant is telling us: is it still in balance? If not, we adjusted this ration."

A greenhouse without people

Asked about what the future holds for AI in the greenhouse, Leonard said the long-term ambition would be to have a greenhouse without people. "That's a long way away, many years. We are doing long-term research to reach that, with control being based only on data instead of models and we will need much more sensors and robotization."

In the mid-term, it's already possible to have autonomous systems take over greenhouse climate control. "Within a few years that's well possible," Leonard expects. In the nearest future, he sees opportunities to improve control in semi-closed greenhouses. "We're already doing tests in tomatoes and lettuce. Some techniques are used just to monitor greenhouses to see if we can help them perform better. Hoogendoorn will be incorporating modules resulting from this research in their climate computers, some of which will already be available within a year."

The grower's perspective

Talking about automation replacing humans is all very well, but what do the human growers themselves think about this? Jan Prins, the third speaker in the webinar, is a veteran greenhouse grower, who is currently the Head Grower at Pure Harvest. Having worked with low, mid, and now high tech greenhouses, Jan knows what he's talking about, and growing in the middle of the desert with Pure Harvest, technology is essential.

Looking back, growers have worked with different sensors (like climate and irrigation sensors) for years, helping them make the right decisions. Now, Jan observes that plant sensors are being used more and more. "From reading the plant just by observations, sensors have now become tools that the grower uses every day. At Pure Harvest, we want to take this to a higher level. For example, we recently installed photosynthesis sensors for more insight into one of the most important processes on this planet."

More than 50 sensors

"In our small farm in the desert," Jan continues, "we have more than 50 sensors, providing a massive amount of data. Without AI and/or dashboards, this would take the grower too much time to analyze." Their strategy is to move to more data-driven growing. "We believe it can help us be more sustainable and profitable."

To help them achieve this, in the hiring process at Pure Harvest they put a lot of emphasis on IT specialists and data analysts, in addition to the traditional grower. Jan expects that traditional growers will also move more to data-driven decisions. "More data will help greenhouse growers achieve more and better results."

"A greenhouse needs a grower like a plane needs a pilot"

Jan concludes by voicing his enthusiasm about the times we're living in, saying the new technologies make things more interesting for human growers. After all, growing is not just about climate and irrigation, there's much more to it than that. "You can't just buy a greenhouse, plug the power into the socket and go to the beach. A greenhouse needs a grower like a plane needs a pilot. An airplane can fly itself, but the pilot is still there for good reasons."