A plant responds to low humidity by making large leaves. This means

that low humidity creates a vegetative plant and that a grower can create a more generative plant by maintaining a high humidity. But how high can he go? The surprising answer is that in a semi-closed glasshouse, he can almost never go high enough, and Godfrey Dol, an expert on cultivation in semi-closed glasshouses explains why that is.

First, let’s define Absolute Humidity (AH), Humidity Deficit (HD) and Relative Humidity (RH). AH is the maximum amount of water in grams that can be contained in one cubic meter of air. HD is the number of grams of water that must be added to a cubic meter of air to reach AH. Relative Humidity is the amount of water vapour present in air expressed as a percentage of the amount needed to reach AH.

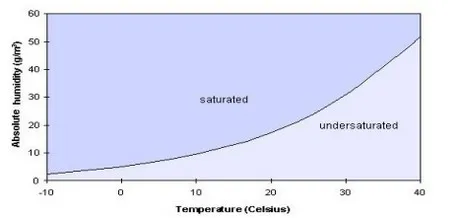

Figure 1; Absolute Humidity

Figure 1 shows the AH of air. The graph makes it clear that warm air can contain more water vapour than cool air. People experience this emphatically when on a hot summer afternoon, a cold front cools

warm humid air resulting in a tropical downpour caused by the fact that cold air cannot contain as much moisture as warm air.

The graph shows that 30-degree Celsius air can contain almost twice as much water than air at 20 degrees Celsius. The day-time temperature in the glasshouse varies between 20 and 30 degrees

Celsius. At these temperatures, a slight change in temperature or humidity can create a large difference in HD. For instance, decreasing the humidity from 75% to 65% at 25 degrees Celsius increases the Humidity Deficit from 5.8 to 8.1 gr/m3.

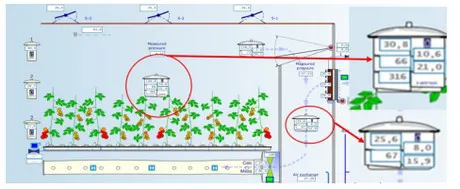

Figure 2; Conditions in the glasshouse at 85% fan speed.

To consider the true reality of humidity look at figure 2. The glasshouse is at 31.4 degrees Celsius and 63% RH. Compare this to 30.8 degrees Celsius and 66% RH in figure 3. At first sight, it seems that the example in Figure 3 would be preferable as the HD is lower and the temperature is cooler. But looking closer, will make people find out that the fan speed in figure 3 has been turned up from 85% to 100% in an attempt to cool the glasshouse. The air was pushed through the climate chamber too fast and the water in the pad wall did not get a chance to evaporate resulting in air with a lower water content being blown into the glasshouse.

Figure 3; Conditions in the glasshouse at 100% fan speed.

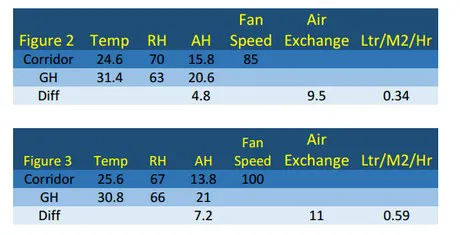

In a semi-closed glasshouse, growers can measure the difference in AH between the air coming into the glasshouse and the air leaving the glasshouse. If they assume that the transpiration of the plants is

responsible for the difference, they can calculate how much the plant transpires.  Figure 4; Calculating the transpiration rate.

Figure 4; Calculating the transpiration rate.

The transpiration rate is obtained by multiplying the difference in AH between incoming and outgoing air, multiplied by the air exchange rate, multiplied by the height of the glasshouse. In this example, the glasshouse is 7 meters tall. The calculation for the change in air volume at different temperatures must be also adjusted, but this has only a tiny impact on the result.

Figure 4 shows that the plants in Figure 3 added a whopping 0.59 Ltr/M2/Hr to the glasshouse air. Compare this to almost half that amount at 0.34 Ltr/M2/Hr in the example for figure 2 and one realises, nothing is like it seems in the semi-closed glasshouse when it comes to humidity.

The main difference between the two situations is caused by the lower AH of the air entering the glasshouse in figure 3. Reducing the transpiration rate at the conditions in this real-life experiment, helps the plant perform better. In a semi-closed glasshouse, growers must take the AH of the air entering the glasshouse into consideration.

In a conventional glasshouse, growers should do the same, however, it is much more difficult to ascertain the air exchange rate. This is another great advantage of the semi-closed glasshouse, according to Godfrey. The air exchange is (virtually) nondependent on the outside conditions.

After the last post, a question was asked if Vapour Pressure Deficit (VPD) is the measurement growers should use to assess the climate. To be useful any measurement needs to meet three criteria. It needs to measure correct all the time, be representative of the area that it measures, and growers need to be able to attach guidelines to the measurements, so the grower knows if it is too high or too low.

VPD measurement through infrared meters is a great tool to provide the grower with information, but the question needs to be asked whether the infrared measurement of a dozen or so plants is a

good reflection of a 1-hectare compartment.

Growers have come to rely on temperature and humidity

measurement in a glasshouse as a good way to assess the climate because temperature and humidity are homogenous. In addition, the guide levels for VPD are 0.5 to 1.5, but Godfrey has seen plant

stress, or too much vegetative growth well within these guidelines. "I compare the infrared meters with moisture sensors or scales to help with irrigation management. It provides the grower with much

more insight into what really happens with the plant, but no one irrigates based on these measurements only.

Personally, for a semi-closed glasshouse, I would like to see the climate computer calculate the transpiration rate based on the difference in AH between the climate chamber and the glasshouse, corrected for fan speed, like the example given in this post. This would be the ultimate guideline in whether we are giving the plant a vegetative or generative impulse, and if we make the plant work too hard."

This article is part of a series about growing in a semi-closed greenhouse. Read here more about no-go's for semi-closed glasshouses, cooling, the difference between semi-closed and pad and fan glasshouses and how to prevent momentum and becoming a crop to vegetative.

For more information:

Glasshouse Consultancy

www.glasshouse-consultancy.com

Godfrey Dol

LinkedIn

godfrey@glasshouse-consultancy.com

+81 80 700 94 006