This year's World Food Prize was awarded to two pioneers of crop diversity conservation: Geoff Hawtin and Cary Fowler. Both have been champions of genebanks – including the eleven that are run by CGIAR centers – and they were the driving force behind the creation of the Svalbard Global Seed Vault.

They have helped ensure that hundreds of thousands of crop varieties are safely conserved to give farmers and scientists options as they strive to grow nutritious food in a changing climate. But not all crops are equal.

Storing plant diversity as seeds is relatively straightforward. Once they have been collected, sorted, and cleaned of diseases, orthodox seeds can be dried out, packed in a sealed container,r and stored in a cold room (typically at -18°C).

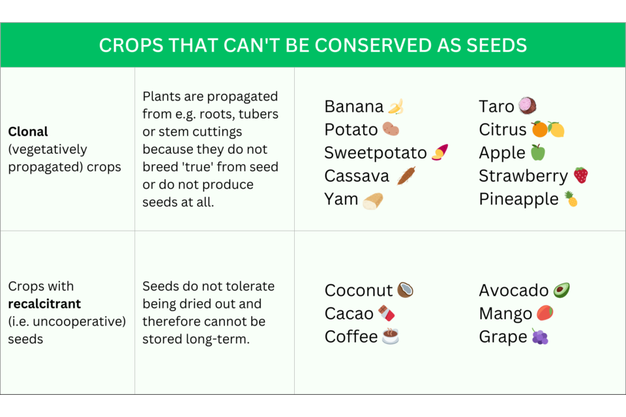

Sadly, this technique does not work for many of the plants we eat. The list includes five of humanity's ten most important crops – potato, cassava, sweet potato, yam, and banana – and several plants that both farmers and consumers would sorely miss if we could no longer grow them, such as cacao, coffee, coconut, apple, pineapple, and orange, among many others.

Global annual production of crops that cannot be conserved as seed is estimated to be worth at least US$100 billion annually.

The diversity of these crops has traditionally been looked after as plants and trees in the field. This on-farm conservation will always be important. It ensures that the diversity is being used and consumed, and it allows the plants to continue to evolve to changing conditions. Due to the complexity of the conservation of these crops, many genebanks also maintain their diversity in controlled experimental fields.

But it leaves the plants vulnerable to threats ranging from diseases and land use changes to cyclones and war.

Many collections have already been wiped out. In Togo, up to 37% of yam cultivars are believed to have been lost, and in Samoa, the national taro collection was destroyed by leaf blight.

An alternative, complementary approach is to conserve these crops as tiny plantlets in test tubes in genebanks, often under "slow growth" conditions. This in vitro technique makes it possible to bring diversity together in one place, making it much easier to use in research and breeding.

Cassava plantlets stored in vitro at the Future Seeds genebank in Colombia

Cassava plantlets stored in vitro at the Future Seeds genebank in Colombia

However, the plantlets outgrow their test tubes after periods of one to three years and so must be frequently cut back and transplanted into new tubes. This means the samples are vulnerable if staff cannot easily access collections, as happened in many genebanks during Covid-19 lockdowns. It also means that they are under significant risk of contamination and/or mixture, due to intensive manipulation.

Due to these challenges, as many as 100,000 unique examples of crop diversity are at risk of being lost. We urgently need another solution to protect this diversity and ensure that it is available to future generations.

A solution could be cryopreservation.

This technique, developed in the medical world, makes it possible to store plant material in liquid nitrogen at -196°C. The ultra-low temperatures halt cell metabolism, meaning that samples can be stored for decades and potentially centuries.

The material is stored safely in metal tanks, comparable to big thermos flasks, and is protected from the risks inherent to the field or in vitro conservation. Cryopreservation also saves a lot of space – a tank the size of a wine barrel can hold thousands of samples.

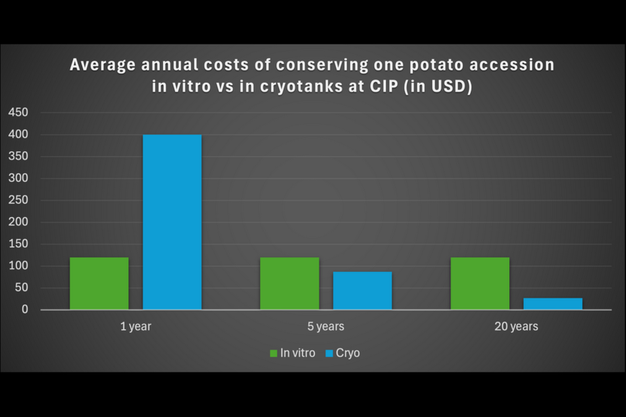

And while there are significant up-front costs in getting the material into storage, there are major savings over the longer term. When compared to in vitro conservation, the initial outlay is recovered in between 5 and 15 years, depending on the crop.

Cryopreservation also provides a viable, efficient way of backing up the collections stored in genebanks. Rather than multiplying and replacing plantlets kept in test tubes as safety duplicates every year, the cryopreserved material can be duplicated just once and then kept in a cryo hub in another location.

That would offer these hard-to-conserve crops a similar level of protection to that which Svalbard provides for seeds. We would be able to recover and regenerate any lost material as happened when ICARDA's collections were damaged by conflict in Syria.

CGIAR centers are already using cryopreservation to protect crop diversity, including 4,500 varieties of potato and 550 of sweet potato at the International Potato Center (CIP), 1,350 types of banana at the Alliance of Bioversity and CIAT, and 400 samples of cassava and 100 of yam at the International Institute of Tropical Agriculture (IITA).

These centers have shown that it is possible to line up all the necessary pieces: a regular supply of liquid nitrogen; just-in-time delivery of good quality, clean plant material; and highly-trained teams to excise and store the samples.

The CIP team has developed detailed protocols and step-by-step guidance for potatoes, just as the Alliance of Bioversity and CIAT team have done for bananas. Other CGIAR genebanks are following suit on cassava and yam.

A model approach has also been developed for partnering with communities to rescue and conserve crop diversity from farmers' fields.

In a project funded by the UK Darwin Initiative, farmers' sweet potato varieties in Zambia and Mozambique are gathered for disease cleaning in a phytosanitary hub. The cleaned material is then multiplied up by national partners and disease-free planting material is returned to the farmers for planting, with the unique samples sent for long-term conservation in a cryo hub.

These examples show that cryopreservation can be successfully implemented and offers a long-term solution. The next step is to develop a global movement to scale up and protect hard-to-conserve crop diversity before too many more varieties are lost forever.

Source: CGIAR